My First Hamam Experience

Kılıç Ali Paşa Hamam: contemplation and cleaning in a 16th-century Turkish Bath

I was planning my first visit to one of Istanbul’s many Turkish baths, and, well, I was a bit nervous. What if I committed a social, cultural or–heaven forbid–religious faux pax. What if I wore a bathing suit when I was supposed to be naked? Worse, what if I was naked when I was supposed to wear a bathing suit?

What did I know? I was a Jewish kid from Boston about to partake in a traditional Islamic experience.

I’d spent considerable time in Austria and Germany and knew that nudity was not just allowed but also required in the sauna/whirlpool/steamroom areas of most spas and even public baths. At the same time, I recalled giving advice to a friend when we were just across the border in Slovakia. How different could customs be just a few miles away from each other?

Apparently, quite a bit, since his nudity made quite a scene. I don’t think he trusted me ever again.

With that memory, I briefly considered taking a guided tour to the hamam, where the guide would advise me on the process and reduce the likelihood of embarrassment or an international incident.

Frankly, a bathing coach seemed a bit excessive. My biggest concern was a binary situation: suit on or suit off. So I decided to figure it out and go on my own.

Meeting the owner and visionary

But not until I spent time with Nureddin İren, the owner of the Kılıç Ali Paşa Hamam, one of Istanbul’s most traditional and finely restored Turkish baths.

A few hours before my hamam appointment, I sat outside with İren, the man who restored and now runs this extraordinary 16th-century bathhouse. For nearly an hour, he told me about the structure’s history and the ritual of Turkish bathing.

He explained how the historical roots are traced back to the Roman bath. In the 16th century, the Ottomans introduced new elements including advanced heating systems and running water.

He contrasted the hamam experience with other bathing cultures like the onsen in Japan, banya in Russia, and Finnish sauna. Beyond the hamam’s religious connections, he noted the unique feature of being washed by someone in a hamam.

Hamams were often built next to mosques so that worshippers could bathe before praying. They also served as gathering places and were central to social life.

İren’s connection to the hamam is deeply personal. A former corporate professional, he turned his attention to cultural heritage conservation after becoming captivated by the historic bathhouse.

The restoration

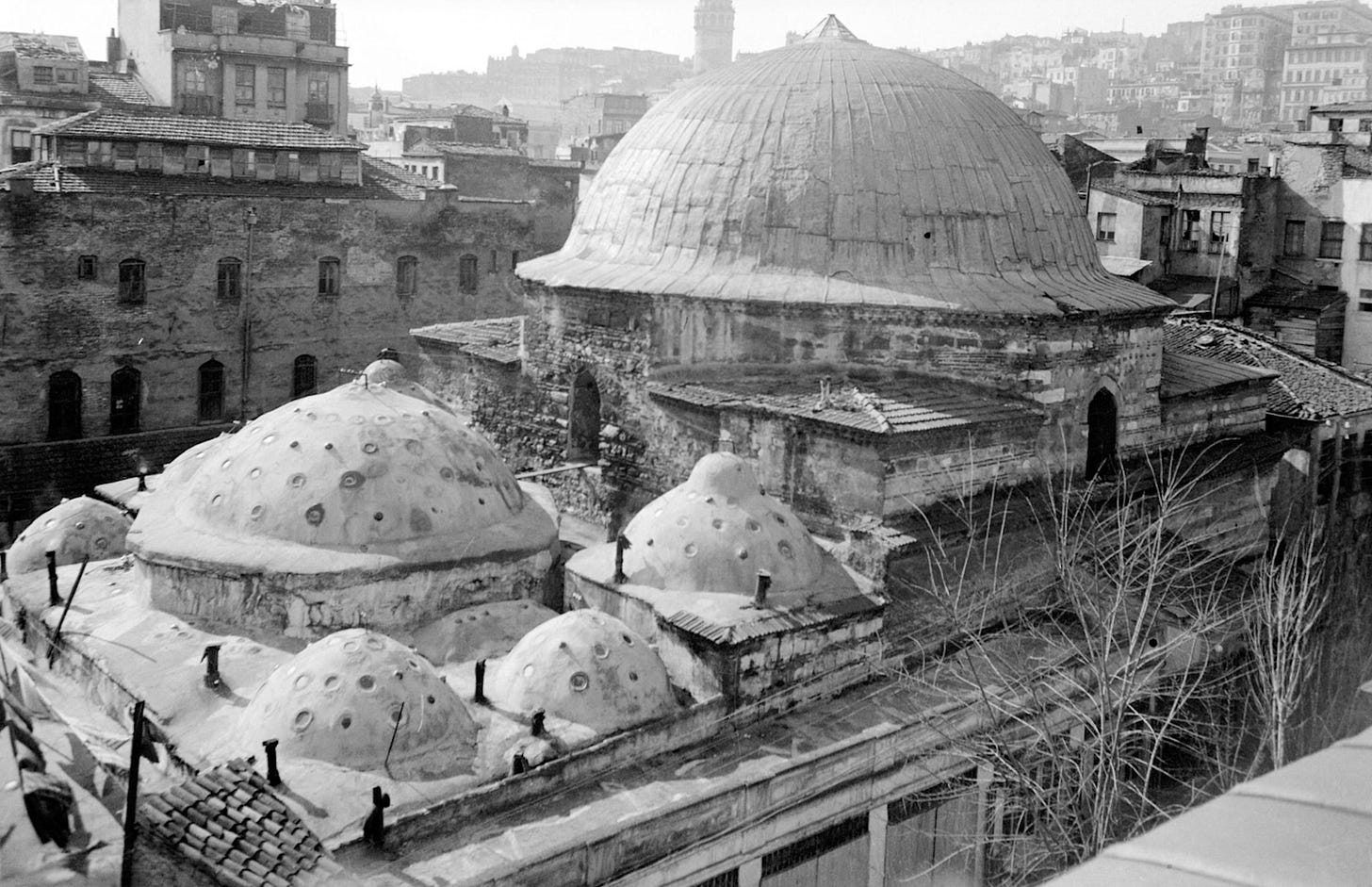

He purchased the hamam in 2005 when it was in a state of severe disrepair. He led a painstaking, privately funded seven-year restoration that was completed in 2012.

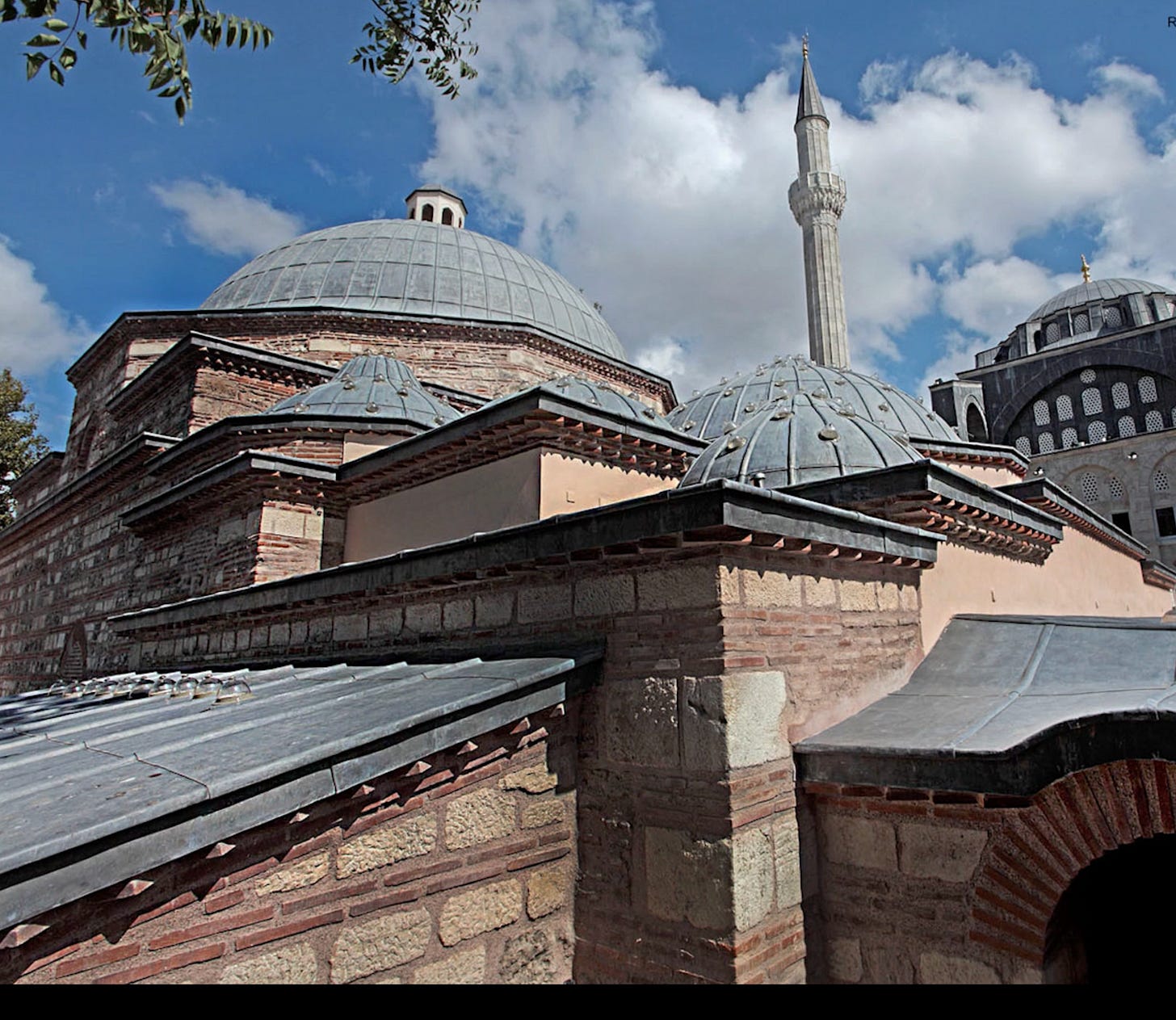

I’ve looked at before, during and after photos and videos of the restoration, and the extent of the work, artisanry and craftsmanship is difficult to comprehend. Indeed, Iren’s efforts were internationally recognized: in 2017, the restoration received a European Union Prize for Cultural Heritage for its faithful preservation and revival of cultural significance.

“We didn’t want to modernize it for the sake of tourism,” he told me. “We wanted to let the building speak with its own voice.”

Its 16th-century start

The Kılıç Ali Paşa Hamam was built between 1578 and 1583 under the direction of Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan and commissioned by Kılıç Ali Paşa, the grand admiral of the Ottoman navy. Kılıç Ali Paşa himself had an extraordinary life. Born Giovanni Dionigi Galeni in Calabria, Italy, he was captured and enslaved by Ottoman corsairs, converted to Islam, and rose through the naval ranks to achieve the Ottoman Empire’s top naval position.

His commissioning of this bathhouse complex and adjacent mosque close to the waterfront reflected both his devotion and his status. The hamam was designed as a functional and spiritual companion—a space where sailors, traders, and mosque-goers could cleanse their bodies and prepare their minds.

Factoid 1: An enslaved Miguel de Cervantes helped construct the Kılıç Ali Paşa Mosque. In his “Don Quixote de la Mancha,” he later referred to Kılıç Ali Paşa disdainfully as “El Uchali,” Turkish for "the scabby renegade."

Istanbul has no shortage of historic hamams, each with its own character. Yet, Iren stressed, none matches the understated elegance of Kılıç Ali Paşa Hamam with its maritime origins and proximity to the mosque anchoring it in Istanbul’s layered past.

The Kılıç Ali Paşa Hamam exemplifies Sinan’s mastery. The symmetry and layout encourage calmness, guiding bathers from the cooler outer rooms into the progressively warmer interior.

Approaching the hamam

As I approached the hamam, the aroma of Turkish coffee mingled with the salty breeze of the Bosphorus. The call to prayer echoed through alleyways.

The hamam’s façade is understated but welcoming. I entered through a modest door and found myself in a domed welcoming area, softly lit, with wooden balconies. Attendants moved quietly between guests. Some guests sipped tea. Others spoke in low voices. The atmosphere was warm, restful and serene.

A personal attendant welcomed me, handed me a cup of homemade fruit syrup, and showed me to my private locker cubicle. He handed me a pestemal (thin cotton towel) and wooden slippers and gave me a highlights reel preview of the next steps.

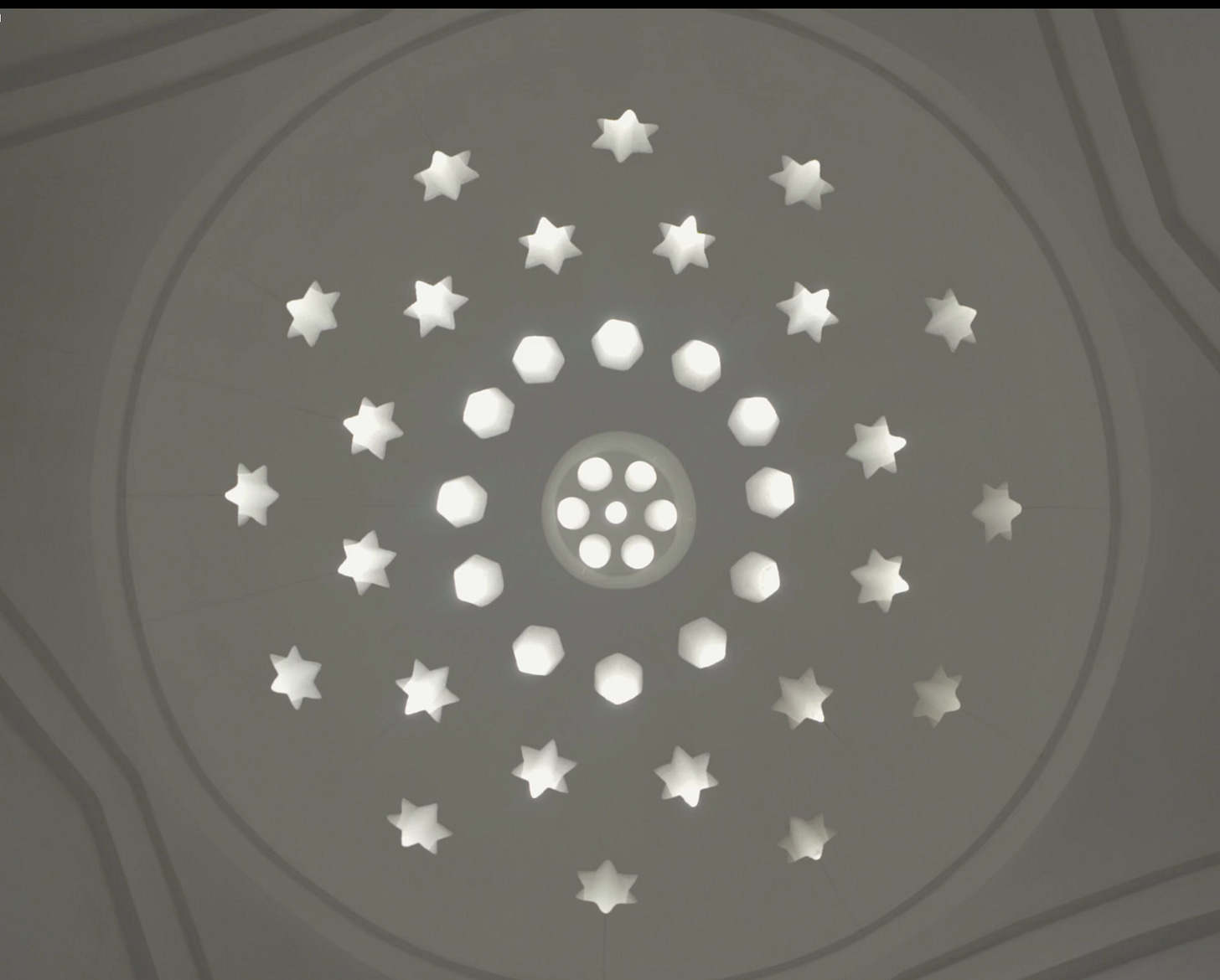

I disrobed, wrapped the pestemal around me and descended into the warm core of the hamam. The scent of wet marble and soap surrounded me, suspended in mist. The attendant guided me onto the göbektaşı, a vast heated slab that radiated deep, penetrating warmth. Overhead, a domed ceiling was perforated with geometric shapes plugged with glass. These let in natural light in carefully arranged patterns, creating a diffused, celestial glow.

The hamam’s symmetry, the curvature of the dome, and the use of sound-absorbing curves and light-reflecting surfaces—all were designed to cultivate a sense of internal quiet.

“Architecture is not just structure,” İren had said. “It is rhythm. It is silence. It is meaning.”

Broiling on the göbektaşı

For nearly 20 minutes, I simply lay still. The heat softened my skin and slowed my breath.

At about 17 minutes, my typically irrational abandonment issues kicked in and disrupted my internal quiet. What if he forgot me, like the acupuncturist who left me like a naked pincushion when she forgot me and left for the day? Damn those intrusive thoughts when I’m trying to achieve Nirvana (yes, I know Nirvana is an element of Buddhism and Hinduism, not Islam).

My conscious rational self countered with, “But what’s the worst thing that can happen?”

Before I could start compiling a list and ruin the mood, a telah—a professional bath attendant—approached wrapped in his own pestemal. My heart rate slowed in relief.

He noticed my turtle-like struggle to bring myself upright on the slick surface and rescued me with an outstretched arm.

He also noticed my failed wrapping technique with my pestemal. He smiled at me, loosened it, then wrapped it more securely. He gave a motion with his hands that in another setting might have been accompanied by a “Ta-da!”

Exfoliation extraordinaire

He next examined my skin for any sensitive areas or abrasions. Finding none, he donned a kese, a coarse wool mitt used for exfoliation. He scrubbed with rhythmic strokes, lifting layers of dead skin.

He then poured warm water over me from a copper bowl. The sound was soft and echoing—the splash, the scrape, the sigh of steam, my own sighs.

Soap washing followed. The telah took a cloth bag filled with Hacı Şakir soap and whipped it through the air and water until thick, luscious bubbles billowed out.

Factoid 2: Hacı Şakir soap is now owned by Colgate-Palmolive.

Foam so dense a cat could walk on it

The foam was so dense that I joked to myself that a cat might walk across it without sinking. At very least, a mouse. He spread it across my limbs, using a cotton lofa to massage and cleanse. The sensation was slippery, light, and oddly luxurious. I could definitely get used to this.

İren had explained much of this in advance. “You don’t just wash in a hamam,” he said. “You submit to something older than you.”

He emphasized the cultural tradition: that the telahs once operated as freelance artisans, not employees. They were paid by their clients with gold coins.

He explained how the water must always flow, according to Islamic principles. How the space was built not just for cleaning, but for contemplation.

Make a wish

The telah stretched my arms over my head and behind me, as if making a wish. I grimaced but endured. After several moments, I felt a slight pop and a release.

Interestingly, I’d been avoiding going to the orthopedist for what I’d self-diagnosed as frozen shoulder. I didn’t realize it until later in the evening, but I’d regained nearly complete mobility.

The session ended with a hair wash and a series of final rinses, each with a splash of water cooler than the last. My body tingled. My skin felt new. I felt connected to centuries of tradition.

He then wrapped me in dry towels and guided me to a quiet resting area. There, I reclined with a glass of water, surrounded by hidden muted voices and the occasional clink of teacups. The transition from steam to stillness was meditative. The high dome of the warm bathing chamber had seemed to amplify and slow time; now, back in the cool air, time resumed its normal rhythm.

“Some people find healing in it,” Iren had told me. “Others just get clean. But when the telah is skilled—and when the guest is open—there’s something deeper.”

A choreography of steam, stone, water, soap, silence

Whether or not I reached that depth, I don’t know. But I emerged from the experience profoundly relaxed, aware of my body and my breath in a new way, and connected to centuries of tradition. The ritual had unfolded like choreography: steam, stone, water, soap, silence.

As I descended the steps and crossed the lobby, an attendant stopped me.

“I’m sure Mr. İren explained that the hamam experience is not the same as a massage experience,” he said. “But we do offer massages separate from the bath.”

I raised one eyebrow.

“If you have another hour, Mr. Iren has arranged a massage for you as well, his compliments.”

Well, as they say, when in Istanbul…

But do I keep the suit on or off?